First published in The Record, March 18, 2017

In Allen Ginsberg's hometown, a poet keeps the Beat Generation alive

Don Kommit in a favorite haunt, drinking espresso and reading the funnies. Photo: Danielle Parhizkaran/Northjersey.com

What singularity of purpose, what madness, what lightning rage of consciousness drives Don Kommit – still! – to paint, to write, to draw, today, 60 years after this whole Beat Generation thing began?

Because, you see, Kommit knew them all. He partied with Jack Kerouac. He sketched Bob Dylan in coffee shops. He read poetry on television with Allen Ginsberg. He was there at the almost-beginning, in 1960, wearing a blue beret and looking for girls and adventure in the still-quiet streets of Greenwich Village.

Now Kerouac is dead. Ginsberg is dead. Dylan is off recording big-band hits. But Don Kommit hasn’t moved an inch. He’s still right here, in downtown Paterson, aiming the aerial antenna on the roof of his mind toward heavenly frequencies, transmitting divine radio waves and random bits of dirt down through his fat fingers and into an Apex paper sketchbook that he bought at Paterson’s Supermundo discount store for $2.49.

“It’s exciting. I love the action. The doing,” said Kommit, 78. “You’re living in that known-unknown place. Whole streams of consciousness pour right through me, and I run to catch it on the page.”

Kommit’s art does not earn him much money, and it has not made him famous. Even among Beat movement experts, Kommit remains virtually unknown.

“No, I haven’t heard of him,” said William T. Lawlor, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and the editor of Beat Culture, an encyclopedia of Beat artists and artwork. “With the Beats, that’s not unusual. It was accepted that broad recognition probably wouldn’t come, and it was more important to be honest, to bring the subconscious mind to the surface.”

But to his friends in the small solar system of North Jersey artists, Don Kommit is a legend. He lives in Paterson’s oldest surviving factory building, erected in 1813 between the Passaic River and the water raceway, which powered the city’s early mills.

This landscape of brick and water serves as the inspiration and subject for much of his art. And like the old mills, Kommit seems worn but immutable, like an industrial-age dynamo that still manages to twirl, converting the rushing current of his life into sparking electricity.

“Don has always inhabited that spirit of [Alexander] Hamilton at the Falls, that optimism, that can-do attitude,” said George Pereny, a poet and teacher who has known Kommit for 40 years. “That spirit is Don. He is Paterson.”

Before the Beats, before Ginsberg’s "Howl" and Kerouac’s "On the Road," Don Kommit lived the Paterson of his imagination. He was born in the city in 1937, and all of his male relatives worked as plumbers or tailors.

But at night they were artists, illusionists. His father was a masterful tap dancer, Kommit said. His Uncle Carl and Aunt Mamme belonged to a Yiddish theater troupe, and they performed plays inside their tailor shop in Haledon, using piles of laundry as props.

“It was all in Yiddish, which I didn’t really understand,” Kommit said. “But I did feel what was going on because it was very demonstrative, with the whole body. It was always just fantastic.”

Kommit sat for hours in Paterson’s Rivoli and the Plaza theaters, immersing himself in Westerns. When the movies finished, he tumbled outside with his friends to improvise stunts. In summer, they turned bathtubs into rafts and sailed down Molly Ann Brook, staging mock battles. In January, they piled discarded Christmas trees into a bonfire, placed mattresses on either side, and jumped through the flames.

A man used to lead a horse-drawn cart through Paterson, selling rags. Kommit and his friends curled their fingers into six-shooters and staged mock ambushes.

“We would jump on the horse and pretend to rob his stagecoach. He would crack his whip at us,” Kommit said. “We staged every fantasy.”

Kommit’s made-up worlds extended to the page. He had little interest in schoolwork, but he loved drawing pictures. These scattered artistic impulses gained focus in high school under the influence of two Ginsbergs: Louis, a longtime figure at Paterson Central High School who taught English to Kommit two years in a row; and Louis’s son Allen, who was already gaining notoriety as a co-creator of the Beat Generation.

The movement began around Columbia University in the 1940s, when Ginsberg, Kerouac, William S. Burroughs and others began experimenting with stream-of-consciousness poetry, fiction and painting. Influenced by Buddhism and jazz, they prized spontaneity over polish, a mindset captured by Ginsberg’s motto, “First thought best thought.”

“Don isn’t doing the Hemingway thing of working on a paragraph until he has made this perfectly crafted thing,” said Kurt Hemmer, an English professor at Harper College in Illinois who studies the Beats. “What they create is secondary to how they create. It’s about freeing the mind from social restraints that these artists felt were preventing them from getting out their truest thoughts.”

The Beats also criticized postwar American culture as obsessed with outward displays of success. Instead, they embraced small-time criminals and addicts, experimented with drugs and casual sex, and developed a fashion style that outsiders criticized as slovenly.

“When you surrendered your individuality to conform to the expectations of the corporation, all of that was distasteful to the Beats,” Lawlor said. “They wanted an alternative lifestyle that would allow for broader experience.”

The art, the adventure, the women – Kommit was attracted to all of it. After graduating from high school in 1956, he enlisted in the Marines. He loved the camaraderie but missed painting and poetry. He returned home in 1960 and started making pilgrimages to Greenwich Village, where he soaked in the culture of the Beats, and started writing, painting and drawing his spur-of-the-moment thoughts in sketchbooks.

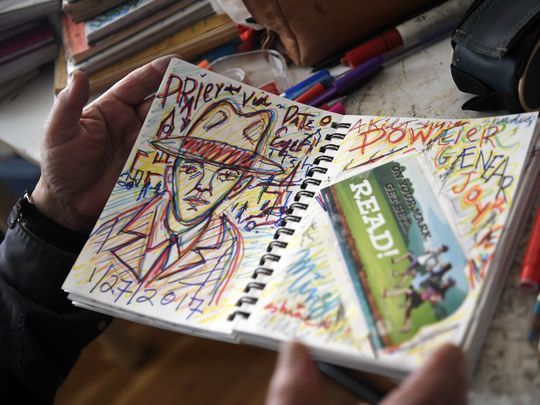

Kommit captures his flight-of-fancy thoughts and spur-of-the-moment inspirations in notebooks. Photo: Danielle Parhizkaran/Northjersey.com

“There were years when I didn’t put it down, and I was angry and miserable,” Kommit said. “Once I started putting it down, religiously, I just was so much happier. It’s like my therapy.”

He bounced around, attending William Paterson University, Rutgers and the University of California-San Diego, and moved to San Francisco. Then he returned home for good, renting an art studio four blocks from the Great Falls and working as a substitute teacher in Paterson's public schools.

Maybe it was inevitable Kommit would grow old here. In some poems he renames Paterson “Pater-swoon,” and the name is true: He swoons over this place. His sketchbooks are filled with drawings of Paterson’s underworld, a land of pool players, poker rooms and hustlers.

A sketchbook from 1974 contains a pencil drawing of a man in a leather jacket.

“His name was Rex. He was a Paterson cop and he got caught on the take, so he lost his job and just hung out the rest of his years,” Kommit said. “What a great guy.”

Other people in Paterson see the fall of industry and the rise of poverty over the arc of centuries. Kommit sees the city right now, in this snapshot moment: the glow of factory bricks in the sunset light, the swoop and dance of pigeons in the sky.

“Man, we’ve got birds down here. Flocks of them,” he said. “They do aerial ballets. I love them.”

Elder statesman of Paterson artists

Kommit sat before an audience of a dozen people at the Pompton Lakes Public Library one night last month, opened a sketchbook and began reading a poem scrawled in green ink.

“The colt as a conversation, High-Vay-Ace. Desire to succeed in Pater-swoon. Have the energy thrill to revive. Render. Renew. The glue. Ends able. To gather the forces of velocity! Side. Surreal. To revel and ride via y’all. To ray-view the hue. The sky renders the Earth’s abound.”

Kommit speaks in a loud froggy gargle. When he performs, his voice rises and falls theatrically. But his performance skills cannot disguise the fact much of the poem is a blur of non sequiturs.

Occasionally this style leads to awkward moments. After a few minutes of reading, Kommit paused to turn the page. The audience thought he was done and applauded, not realizing Kommit had several more pages to read.

He looked confused for a moment. Then he smiled and closed his notebook.

“In poetry readings, I get swept up in the joy of retelling the story. It’s a kind of trance,” Kommit said later. “But when I’m reading too long, I get tired of it. So then I say, ‘All right, that’s enough,’ and I put it away.”

This is a common theme in Kommit’s life. People with an artistic bent are drawn to him. But something about him, maybe his inward-facing trance, drives others away.

His personal life has been rocky. In school, he was suspended often and held back several times, he said. He and his sister Lois fought for years. He has a daughter who lives in Passaic, he said, and they are close. But he and his other daughter haven’t spoken in years, he said, and he is estranged from his first wife. His second wife died of complications from alcoholism, he said.

“I’ll be riding the bus and have a memory, and I start to cry,” he said. “It reminds me of an old girlfriend, or hard moments in my life. It’s so immediate.”

Photo: Danielle Parhizkaran/Northjersey.com

Other times Paterson reminds him of good times and friends. For decades he has worked with other artists to create plays, movies and events. He helped organize Silk City Poets, a poetry reading group, and the Ivanhoe Artists Mosaic, which hosted music and art events in a former factory. Both groups are now defunct.

All the while Kommit served as an elder statesman, encouraging younger artists. Ellen Denuto, a photographer, remembers inviting Kommit into her home during a busy time in the 1990s. She was so frazzled she had covered an entire window with reminders written on Post-it notes, and she was embarrassed by the display.

“I thought I was cracking up. But he said, ‘Oh! Snowflakes of thought!’” Denuto said. “He accepted us, which helped us accept ourselves.”

For others, the lesson of Kommit’s life took longer to sink in.

“When I was young, I thought Don was this talented guy who couldn’t get his stuff together because he wasn’t famous. I was a jerk,” said Pereny, the poet. “Now I look at him and I realize that’s what’s precious about him. He’s the real thing. He stayed true to his art.”

For Kommit, it means staying true to a central Beat tenet – that the process is more important than the result. In his dedication to "Howl,"Ginsberg cited many unpublished works as inspirations, writing that, “All these books are published in Heaven.”

To Lawlor, the Beat encyclopedist, Kommit’s work keeps that tradition alive, all these years later.

“You don’t necessarily have to be successful as a published writer. You have your daily activity as an artist, and that’s very Beat,” Lawlor said. “Don Kommit’s books are published in heaven.”